Southern Summer Songlines Suite: Country needs Composers

April 23, 2018

More than a cultural feast

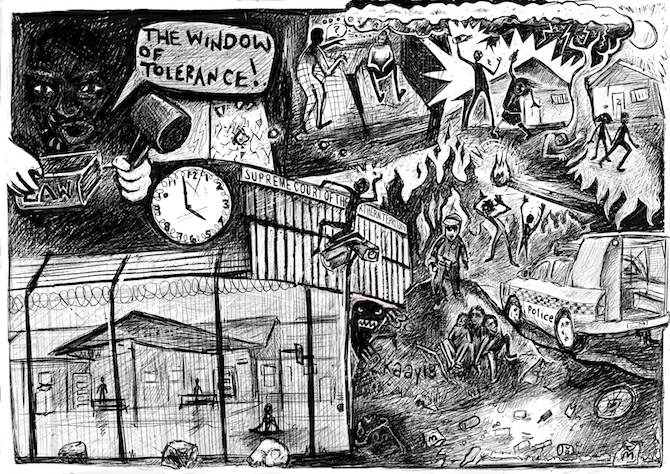

May 11, 2018Image by Tamara Cornthwaite, as published in Alice Springs News Online

The following article by Rainer Chlanda, published in ‘Alice Springs News Online‘ is insightful and essential reading. It humanises the anti-social behaviour of youth in Alice Springs, talking about emotional experiences, fostering psychological understanding and locating the bevaviour in transgenerational trauma.

Youth crisis: broken window of tolerance

By RAINER CHLANDA

I’m writing about what I think are the underlying causes of antisocial behaviour by young people in our town, to acknowledge some efforts that I think are steps in the right direction, and to challenge some common, and what I believe to be unhelpful and damaging misconceptions surrounding it.

The reasons behind all children’s behavior are subjective and complex. Generalizations can be misleading, but as products of a common environment some commonalities can be seen.

I work in a youth support service where I have regular contact with a small number of youths at risk. Inevitably, and importantly, I have contact with their friends and families.

My job involves building strong and trusting relationships from which I can gain insight in to their lives. The framework in which I work teaches me to understand and respond to these young people in the context of unmet needs and the resulting trauma and developmental gaps.

It is from my experience of this work, along with the recent memory of my own growing up in Alice Springs, that I speak.

I see young people go to the street and gravitate towards anti-social behavior for a number of reasons. They may first stay out late at night because home is unsafe, whereas safety and guidance can be found in numbers on the street from peers.

They may begin petty crime, such as stealing food or clothing, as a means of meeting basic needs unmet at home. They are often hungry. What they do is based in necessity and often endures, but in addition to this a culture of behavior emerges.

This “street culture” may also develop out of other less tangible needs such as solidarity, self-expression, and a sense of identity.

Many crimes committed, such as stealing a car for a joy-ride, rock throwing or property damage, have no measurable gain.

But rather than simply calling it criminal, it can be better understood as acts of resistance and protest: Don’t we see this kind of behavior from people around the world when they are deprived of their rights?

A CALL TO THE ADULT WORLD

The group offers acceptance and a sense of belonging whilst the thrill of law-breaking is a way of expressing anger and a call to the adult world to see their vulnerability.

Of course, this cry for help is highly effective; it’s often only when a child is brought into the youth justice system that referrals to support services are made and an intervention takes place.

Simultaneously these actions are also ways of asserting a level of control over their lives; if those responsible don’t meet their basic needs (the kind of fundamental needs recognized in the UN’s Convention of the Rights of the Child) a natural response for a child is to take what is not given.

So whilst clearly defined boundaries and expectations, as well as age-appropriate discipline are important, what these young people (as anyone) need is to feel safe, nurtured, heard, valued, loved, and a sense of belonging.

There is a common trope that the youth are thugs or delinquents and are in need of firm discipline. Some commonly proposed forms are a flogging or to be locked-up.

These responses lack nuance, compassion and any potential to rehabilitate young offenders. Indeed, these types of treatment often reproduce the trauma that gives way to and encourages the (maladaptive) behavior we see.

Violence will only perpetuate violence and incarceration will further criminalize the young person. Although it may be a sure temporary fix for public safety, ultimately the current prison system achieves the opposite.

Despite our juvenile detention system being infamously abusive and damaging, it sadly still better meets some of the needs of its young inmates. It provides security (relative to the outside environments of many detainees) and predictability.

SOME SEE INCARCERATION AS PREFERABLE

A detained child may be deprived of their freedom, a proper education, nurture or a connection to a positive identity and culture. But the set routine, clear boundaries and the reliable provision of food and shelter will have some of them considering incarceration as preferable to living in their communities.

With this comes the obvious consequence of an incentive to re-offend, which is compounded by the galvanizing of the criminal identity formed through networking and bonding with other young offenders in and out of detention.

Especially for young people who are easily impressionable and grappling with a sense of who they are, the mere experience of imprisonment entrenches their identity as a criminal and further orientates them to recidivism.

The NT Government recently announced they would “overhaul the Youth Justice System” with one measure being rebuilding a presumably less prison-like detention centre away from the adult jail and to implement reforms aimed at focusing on culture and connectedness to family.

These changes are surely a step in the right direction, yet if the “system” has done nothing to improve the environment the young person re-enters once released, the revolving doors of the courthouse and detention centre naturally speed up.

TRAUMA CHANGES NEUROBIOLOGY

A crucial consideration for understanding these young people is the impact of trauma on their neurobiology.

Research teaches us that exposure to abuse, especially at a young age, will stunt the development of different regions of the brain as well as hindering effective communication between them.

This is experienced as lacking coherent or rational thought and being prone to impulsivity. The impairment of course varies in degrees of severity, but for example, it is common for a traumatized 13 year old to have a neurological development closer to that of an eight year old.

Children carrying trauma can have a higher than average metabolic rate (heart rate), resulting from the “fight or flight response” being too frequently activated.

In this state their capacity to access their executive functioning region of the brain (responsible for rational thought, planning etc) is reduced and activity in the limbic system (where raw emotion is processed and stress is dealt with) increases.

This combined with blood being channeled away from the brain and towards muscles, as well as the release of adrenalin, calls for an extreme response.

This understanding of a child’s experience of life must guide our response to them, not the least in sentencing if they are before the courts.

A child’s neurology (essentially determining their sense of self) is highly malleable and therefore has excellent potential to be reshaped if the right approach is taken.

One core principle employed in my work is called Strength Based Practice. This means the youth worker simply reflects back to the young person their strong qualities, therefore helping them build a proud identity.

If the young person is misbehaving you frame your objection to that on the basis that the young person is better than their behavior is suggesting.

If a young person is angry or emotionally heightened you know that there is no point in giving instructions as they have very limited access at that time to the region of their brain that receives such information.

Instructions, received as more difficult information to process, will only further push the individual out of their window of tolerance.

You must give calming, repetitive, simple statements until they have deescalated before discussing the behavior.

All professions who engage with youth should receive basic training so that they are trauma informed.

Without the understanding of strategies for effective responses to trauma has children unnecessarily triggered and consequentially experiencing exclusion and punishment throughout their upbringing. This has obvious consequences for a child’s understanding of their place in the world.

SIMPLISTIC BELIEFS ABOUT FAMILIES

There is also a simplistic belief that the families of troubled youths don’t care about them. I instead see loving people caught in a vicious cycle of profound grief, poverty and hopelessness inherited from trauma over generations.

I see people struggling to navigate between the two worlds they’re faced with; between cultural obligations and demands of contemporary society, between lore and law.

Amongst these families I’m privileged to meet people who rise above the immense adversity they’re faced with and dedicate their lives to looking after their often extensive families.

Disproportionately these individuals are women, women who take in the children of relatives who aren’t coping, often in addition to their own. The responsibility of caring for several more lives is compounded by the complex needs these children are likely to possess when coming from dysfunction.

In the event where it is determined that the capacity of those caring for a child can’t be strengthened to a degree where the child’s needs are met, I feel an obvious early intervention would be to channel resources to intensively support those who can provide culturally appropriate and meaningful care to these children.

Currently “kinship’’ placements are sought before a child is removed and taken into care, if successful and a relative registers the care of child they’ll receive an additional family tax benefit from Centrelink. This added income, although necessary, is far from sufficient.

Basic support such as help with grocery shopping, school enrolments, transport to sporting activities and respite for the legal guardian may be the difference between a single responsible adult managing, and them breaking down, leaving the children once again vulnerable.

It is irrational to bemoan such expenditure if it can allow a child to stay with kin as opposed to Out of Home Care or Youth Justice System, both infinitely more expensive and offering less hope for the young person.

Greater efforts should be made to establish care arrangements where young people remain with family. This option is viable in Aboriginal communities in particular as it is highly cultural to take care of a relative’s child.

I’ve supported families in making hard decisions involving their children going to a relative or friend and have seen the result as empowering and relieving.

This is in stark contrast to a child being taken into government care, which, needless to say, echoes the Stolen Generation experience and is highly distressing for both the child and family.

Furthermore, the threshold at which action is warranted needs to be lowered if we are to honor the early intervention principle.

Instead of requiring substantiated abuse before an investigation takes place, a home visit and offer of engaging in voluntary cooperation where the families are empowered and supported in addressing their child’s concern should occur if, for example, they are recorded frequently on the Youth Bus after midnight (a free bus for youth that conveys them home and records the names of all passengers) or observed to be regularly hungry or tired at school.

Of course, I sympathise with business owners who struggle to stay afloat despite incessant break-ins, and residents who don’t feel safe in their own homes.

But to achieve real change our response must not be based on what we feel we have a right to, such as punishment or compensation, but what we can do to help the young, vulnerable and so often traumatized children who are committing many of these offences.

Initiatives such as well devised recreational youth programs, progressive reforms in the Youth Justice System, or social engineering measures around alcohol restrictions, are all important. But as long our youth’s fundamental needs continue to go unmet this issue will remain.